Now that the State of Origin distraction is over, we’re reaching a point in the NRL season where finals hopes are well and truly dashed for some teams, and they turn their attention full time to next season and player recruitment or retention.

As usual in the NRL media cycle, there’s been plenty of speculation about players moving on and teams trying to shore up their weaknesses. There was even a leaked report on how a 17th team would affect all aspects of the league including recruitment. Answer: it would mean they have to work harder. Friend of the site Liam at PythagoNRL has broken down this brilliantly here and is worth a read.

Circling back to recruitment, one of the bigger stories last week was the Tigers looking to “go all in” to sign 29 year old Dale Finucane, who would be 30 by the time the 2021 finals series arrives. This comes a year after bringing in 32 year old James Tamou and 25 year old Joe Ofahengaue to offset the loss of 25 year old Josh Aloiai.

In another move, across the ditch, the Warriors let 26 year old Ken Maumalo go, replacing him with almost four years (!) of soon to be 26 year old Dallin Watene-Zelezniak.

Given the ages of some of these players, this led me to look into some numbers to determine at what age do rugby league players actually peak statistically.

Is there a point in a players career where they are no longer developing statistically and from that point on they are what they are? Just how long should a team expect a 26 year old winger to be productive? Would or should this have any impact on recruitment?

There’s a tendency for clubs to assume players are finished products around 20-22, with players either leaving the game, heading to England or fighting for their career in second tier competitions. For some that is true, but for most positions it appears that their development peak may be later.

If you’re enjoying the posts on this site and want to support independent rugby league content, please consider donating to The Rugby League Eye Test of a value of your choosing via the link below.

To undertake this analysis, we’re going to look at a group of running or attacking metrics by age to determine at what point do players hit their apex as a player. I’ve grouped games played by all players from 2014-2021 into one year age buckets from 18-34, based on the age when a game was played, rather than their starting age during the season.

For example, Latrell Mitchell turned 24 on June 16. His games before that date from 2021 would be in the 23 year old age bucket, whilst games after that date would be in the 24 year old age bucket.

I’ve also put in a minimum game limit of 30 appearances for each age bracket. In doing so I checked how these numbers would change if I dropped the threshold to 10 games or increased it to 80. Interestingly enough, it wasn’t until I dropped below 10 or moved over 90 that any of the numbers changed even slightly as you were capturing fewer players. That said we’re keeping it at thirty because that’s a robust enough sample size to keep things significant and ensure a wide spread of players captured.

And since most positions on a rugby league field have different roles, we’re going to use different sets of metrics for them. For middle forwards we’ll mostly look at runs and metres. For edge forwards the stats are runs, line breaks, and tackle busts. When looking at centres and wings, the stats are runs, line breaks and tries and finally for fullbacks and halves runs and playmaking (line break and try assists).

Keep in mind this is not necessarily meant to show a players physical peak or their high point from an impact perspective, just their statistical peak when their numbers stop improving. Many players will continue to be extremely effective players past these age groups, all that changes is how often they can do it or being able to pick the right spot to do so. Knowing is half the battle.

The point is that by pinpointing the age when players in certain positions peak, you can understand when the development of a player is likely to end, and they’ve moved onto a maturity phase. At a certain age, a player is what they will be and there’s no point expecting or hoping for further improvement. And that age doesn’t always line up with the point when players are moved on from clubs.

It is also worth keeping in mind that the later year players (30+) are more likely to be of higher quality and potentially mudding the stats in those age brackets. Players like Brett Morris, Cameron Smith and Paul Gallen played well into their 30s and the declines for ages over 30 are clouded by those players.

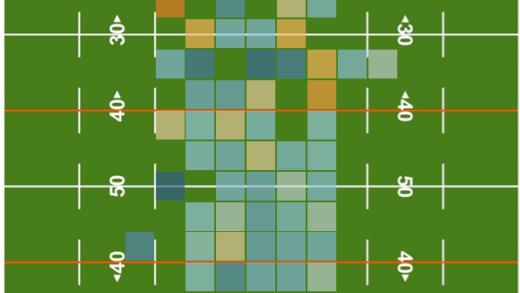

Let’s begin with middle forwards.

Middle forwards

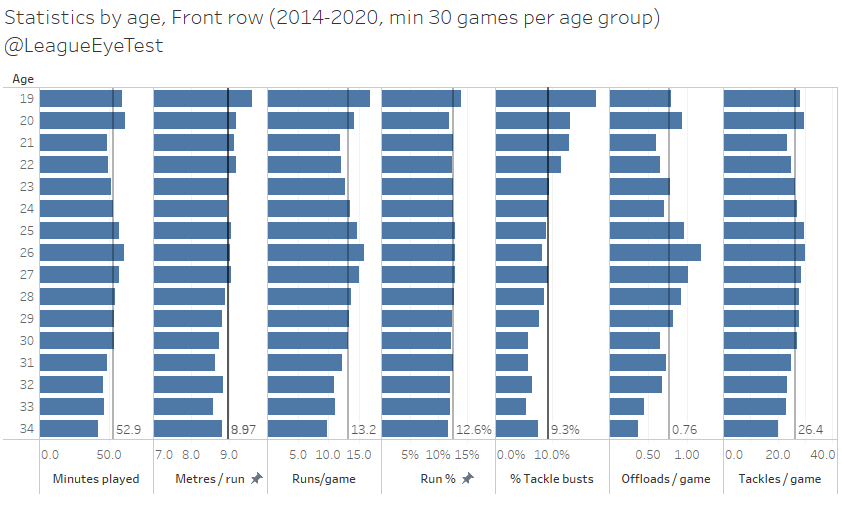

Looking across the most of these statistics middle forwards are peaking at 25-27. At those ages, they’re playing the most minutes, taking the most runs and completing the most tackles. This makes sense as middles mature and move from interchange players to starting forwards. The drop offs from 27 onwards aren’t too severe either until you hit 30.

Middles do tend to start off more as damaging runners of the ball, with higher metres per run and tackle bust % (percentage of runs with a broken tackle), which starts to decline at 23. This is probably due to an increased workload and needing to manage effort with intensity, shown by their run rate (how frequently they complete a run) reaching its highest between 25-27.

Some of this is natural as they play increased minutes as they age. Yet some of the metrics shown like metres per run, Run % and Tackle Bust % aren’t pure volume statistics and aren’t affected by minutes played. Which again indicates why they would decline as minutes increase. It’s hard for players to sustain the same effort in 50 minutes that they were playing at 30 minutes.

An area that does improve later in their careers is the ability to offload. As middles hit 26, they offload the ball more than average until 30 when that drops off to below average.

One thing that doesn’t change much is defensively. I didn’t include the advanced statistic Tackle Rate for middles because it doesn’t change much – around 25-26% each year. So, whilst the number of tackles made per game ebbs and flows as minutes do, the rate at which players are making tackles is steady as players age.

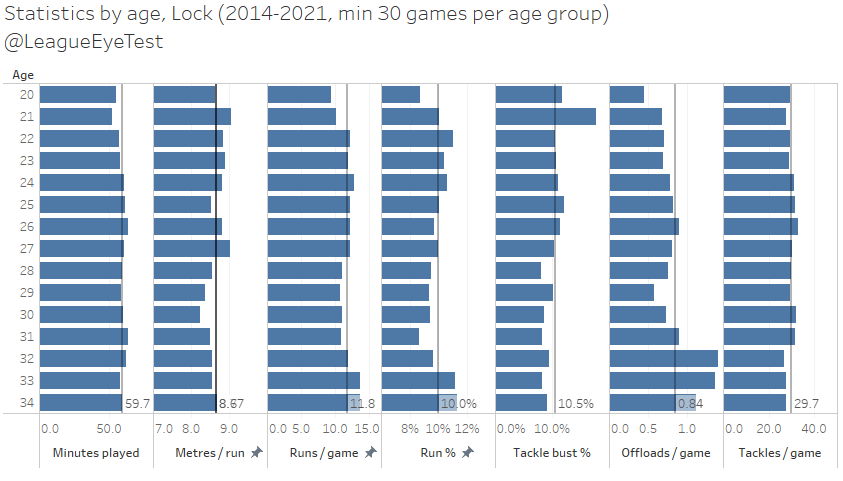

Locks have slightly different profile to props and are much more consistent over time. Like front rowers, their runs per metre drops once they hit their mid-20s, as does their tackle bust %. However, they are running the ball at a lower rate from 27 years old and they’re less likely to be ball players until very late in their careers. Again, keep in mind that these post 30 buckets are affected by a small number of players so those 32-34 offload rates are skewed by likely one or two players.

Penrith recently extended James Fisher-Harris for another four years, and with him currently sitting at 25 it’s the perfect time to lock up one of the best middle forwards in the game as he hits his peak statistical years.

Returning to the Finucane and Tamou examples at Wests, whilst they’re reaching the tail end of their career, there is value in bringing in experienced heads to also assist in developing younger middles like Thomas Mikaele, Stefano Utoikamanu and Alex Seyfarth. Tamou had bucked the trend somewhat in his last year at Penrith, but players finding another level at 30 is the exception not the norm.

It looks though that there may be a market inefficiency in early 20s middles, who may have been discarded earlier by teams expecting them to progress quicker. Instead of bringing in late career middles, it might be better to cast a wider and deeper net looking for young players discarded too soon.

Not only is their output likely to increase as they age, but they would also provide similar production to older players at a cheaper salary. If you can find a bunch of young low cost, high work rate middles, that leaves a lot of salary cap space left to splash around on more impactful players.

Second row

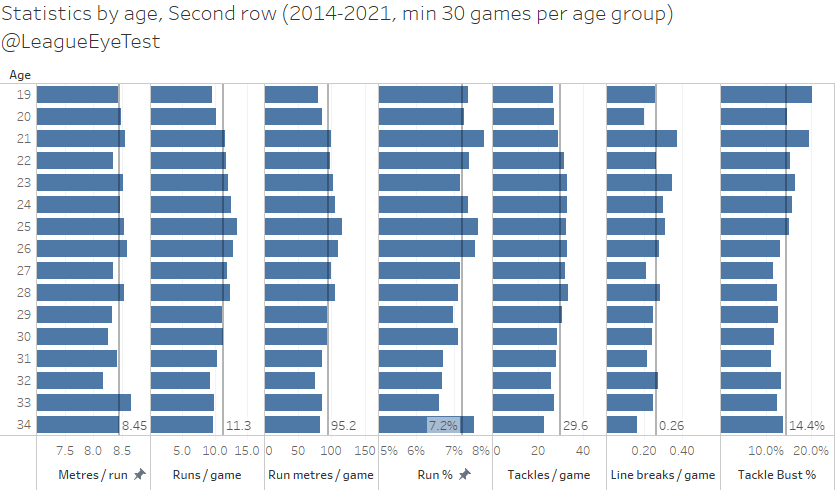

Second rowers share some similarities with middle forwards in that their running involvement inreases in their early 20s and peaks at 26 years old. However their metres per run metric is slightly more consistent over their career and only decline marginally in their late 20s.

Backrowers also tend to be more dynamic earlier in their careers, with line breaks per game and percentage of runs with a tackle bust also hitting their high points in their early 20s. Later in careers, they’re running the ball less and take on more of a defensive role.

Hookers

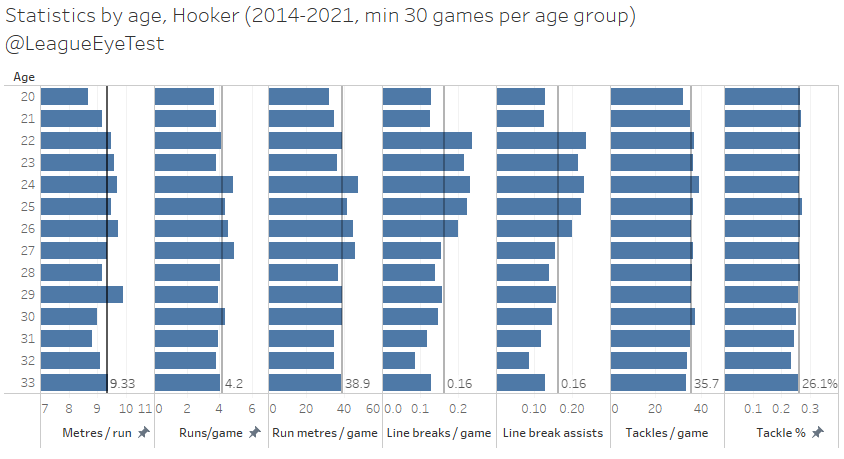

Running involvement for a dummy half peaks between 24-27, as does metres per run which maxes at 29 years old. As you would expect, hookers run the ball less frequently as they pass 27, not only on an overall basis but at a lower rate as well.

The danger of their running game comes a little earlier, from 22-26, when they peak in line breaks and line break assists per game.

Defensively, hookers are making a similar number of tackles no matter how old they are, at about 35 per game. Minutes played is similarly very consistent and actually increases post 30 (mostly due to Cameron Smith), and for this reason I’ve not included it in the chart above.

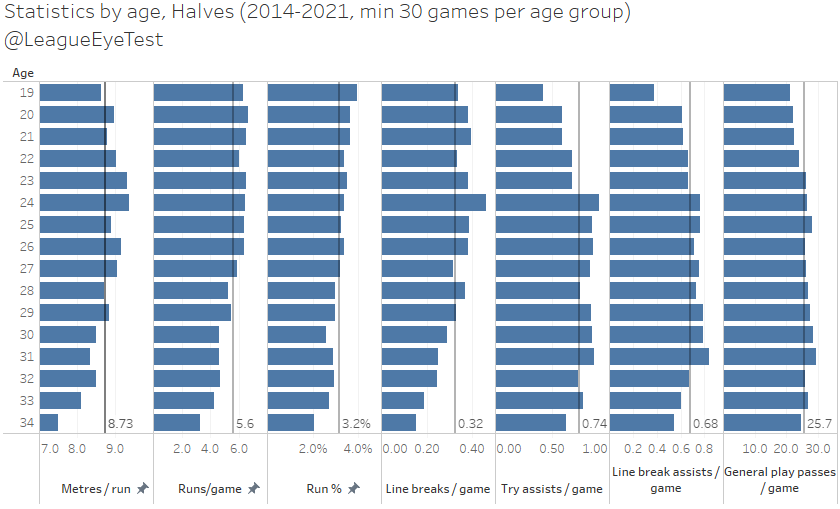

Halves

The halves are a position where age plays a big part in statistical peaks, although it is quite different to when forwards peak and also tends to develop key skills later.

Like other positions, running involvement maxes out at 26 and drops sharply from there. This is probably an indication of players maturing and knowing when to run the ball than any physical decline. Metres per run peaks at 24, whilst runs and run rate is relatively steady until 27 when it declines below average, and it is no coincidence that line breaks per game drops at that point as well. It is in these running statistics where the difference between a five eighth and a halfback occurs, with #6s lasting a year or two longer than 7s for their running peak.

The other big change for halves is that around age 24, they start to really hone their playmaking skills. Passes per game increases as they get more involved in attack, leading to big jumps in try and line break assists per game. It isn’t until they hit their early 30s that these numbers start to tail off. It’s another reason why the Warriors bringing Shaun Johnson home to finish his career makes sense, he’s been in sublime form as a playmaker even if his physical skills have started to decline.

Another reminder that when you’re writing off players in their early 20s, not all of them have finished developing or found their niche.

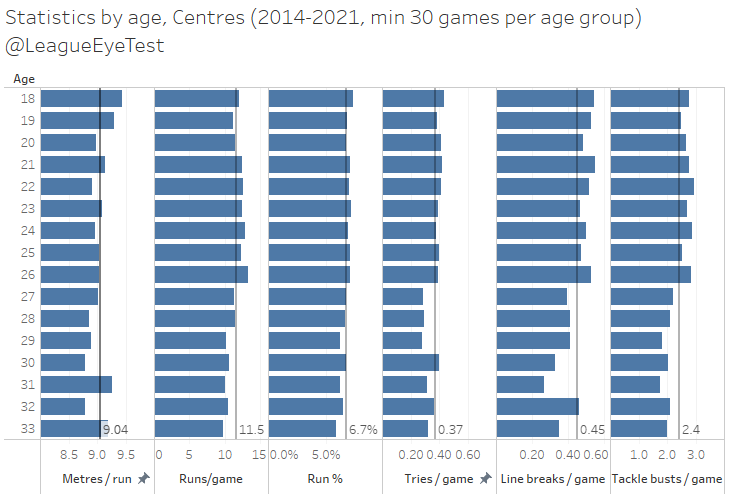

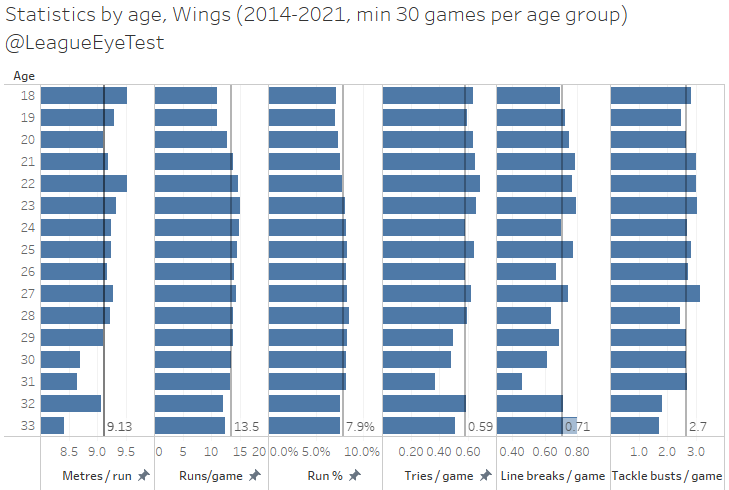

Outside backs

Centres have similar production as they age, peaking at 26. Their running statistics are very similar in late teens to mid 20s, with younger players having a slightly higher metres per run and older players running the ball slightly more.

The biggest drop occurs in attacking stats once they hit 27 when tries, line breaks and line break assists per game all fall off at a fast rate. As mentioned previously, this doesn’t mean that players \are leaving less of an impression on a game, they’re just doing so less frequently.

Wingers have a similar profile to centres but appear to peak a little later at around 27-28, as their run rate increases as they near 30 years old. Their try scoring rate doesn’t drop below average until 29 either, a year later than centres. But as we saw from Brett Morris this season, they can still be very effective into their 30s in the right situation.

Returning to the Warriors example, they may have been right to let Maumalo walk and replacing him Watene-Zelezniak as they output similar numbers. However, Watene-Zelezniak will be almost 30 by the time his deal expires, and the above chart shows that his productivity is likely to decline over the coming seasons.

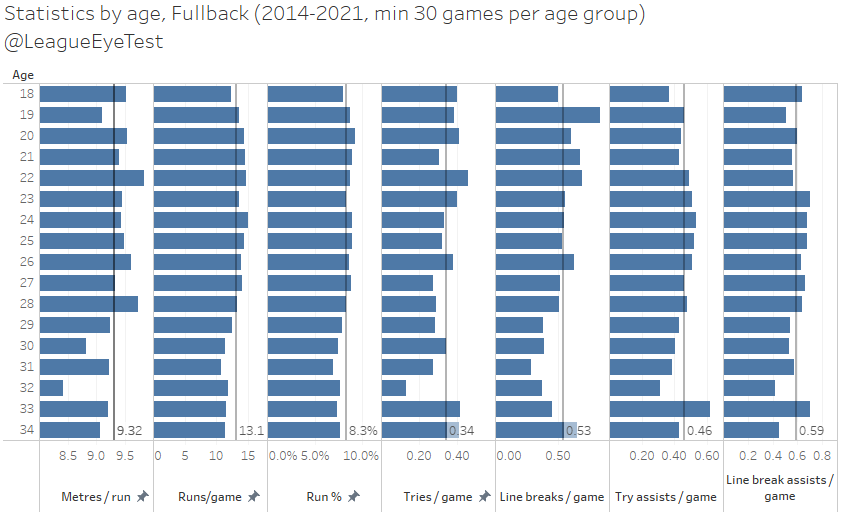

Fullbacks

Fullbacks have an age profile that overlaps between outside backs and halves. Similar to outside backs, their running involvement and output is reasonably consistent from their early 20s until their late 20s, only starting to decline around 28 years of age.

Their attacking impact is more visible early in their careers, with tries and line breaks per game all climaxing before they hit 24. And just like halves, once this drop in pure attacking statistics doesn’t mean a player has hit their peak, it just highlights when they transition from an attacking weapon running the ball to more of a third playmaker role supporting both halves.

3 Responses

[…] of the Rugby League Eye Test, Reynolds is statistically about to go into the downward trend for his career as a playmaker. He […]

[…] League Eye Test put together an excellent piece breaking down the ages of where players peak statistically. For halves, 24 is when the playmaking skills really start to show. Roughly two years later, […]

[…] to Rugby League Eye Test data, once a half, be they five-eighth or halfback, reaches 26 or 27, they run the ball far less. […]